Hungary

Bob’s Dad was orphaned at the age five. When WWI ended his father came home with tuberculosis from serving in the trenches in the Austro-Hungarian Army. At that time tuberculosis had no cure. He died a year later. His widow had to care for three children. My father was the youngest. She ran the family’s tavern in a small village, Kacs, while raising her kids. When she died in 1921, the three kids wound up staying with cousins in other towns. My father was always immensely practical. He didn’t want to go from one distant cousin’s house to another distant cousin’s house, so when he reached the minimum age for signing up for an apprenticeship, 14, he chose to become a baker’s apprentice. His reasoning was that he wouldn’t go hungry if he was surrounded by bread. Bakeries were always warm too. This was in 1929.

Apprenticeships in Hungary were subject to both government and union rules. Bakery owners loved hiring apprentices because they were cheap. The owners had to provide room and board, but no pay. My Dad wound up in the largest bakery in Budapest. My Dad’s “room” was the flour storage area in the basement. He slept on bags of flour. These bags were 50 kilo, or 110 pounds. His first job each day was to carry bags up the steps to the mixers. When I started to work in my Dad’s bakery he taught me how to balance the 100 pound bags on one shoulder and walk them to the mixer. I never had to carry them up a flight of stairs. An apprentices’ job was to do everything no one else wanted to do. My Dad’s last task of the day was to balance enormous loads of baked bread on a bicycle and deliver the bread to households.

While these conditions were Dickensian, my Dad liked it. The bakers’ union had a sports club that let him use a scull on the Danube River and learn Graeco-Roman wrestling, which was popular in Hungary. All things considered, Dad had a favorable view of the baker’s unions in Hungary.

The photo below is the Graeco-Roman Wrestling Team of the Union’s sports club. The arrow points to my Dad. Three interesting things can be observed in the photo. All of the other wrestlers have shoulder straps on their on wrestling outfits. My Dad told me that he couldn’t afford a wrestling outfit. If you look closely at the coach in the back row center, you will see a Jewish Star patch on his jacket. This patch has nothing to do with the yellow Jewish star patches Jews had to wear after the Nazis took over Hungary in 1944. The union and its sports club were Jewish organizations, hence the Jewish star. Lastly, Graeco-Roman wrestling was invented in France in the 1840s based on images of wrestlers from antiquity on vases and in statues. Upper body strength was paramount in this type of wrestling because many of the holds in regular wrestling were not allowed. For example, you could not grab your opponent’s legs. Carrying those 110 pound flour bags helped my Dad develop the upper body muscles that are clear in the photo.

The United States of America

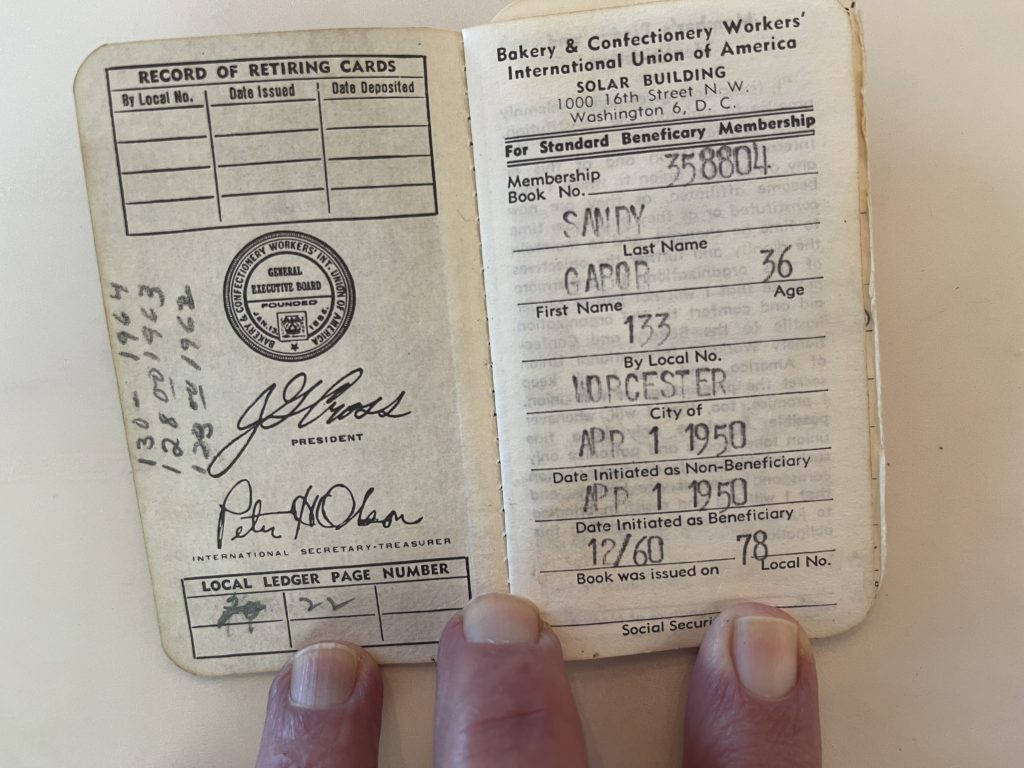

After the war my mother and father left Hungary for a displaced person’s camp in Germany, Bergen-Belsen, where I was born in 1947. In 1949 the three of us were able to emigrate to the United States and settle in Worcester MA, were Dad got a job at the Widoff’s Bakery. This bakery was a union shop, so my Dad had to join the Bakery and Confectionary Workers International Union Local 33. The “International” in its name was because the union had Canadian locals. This union was one of the earliest craft unions in the United States. It started in 1886.

After my parents became US Citizens in 1955, our family (now four with the addition of my sister) moved to Detroit, which was bustling at the time. The Big Three automobile companies were in their heyday. Again, the bakeries were union shops, so my Dad joined the local branch of the same “international” union.

My father took an active interest in his local union’s affairs. He even memorized Robert’s Rules of Order so that he could make proper motions at the local’s meetings. Around 1965 my father bought a small bakery, that was part of the local Model Bakery chain. It was at the corner of Chene and Frederick Streets in Detroit. To distinguish it from the other Model Bakeries, it was renamed the Frederick Model Bakery, after the street.

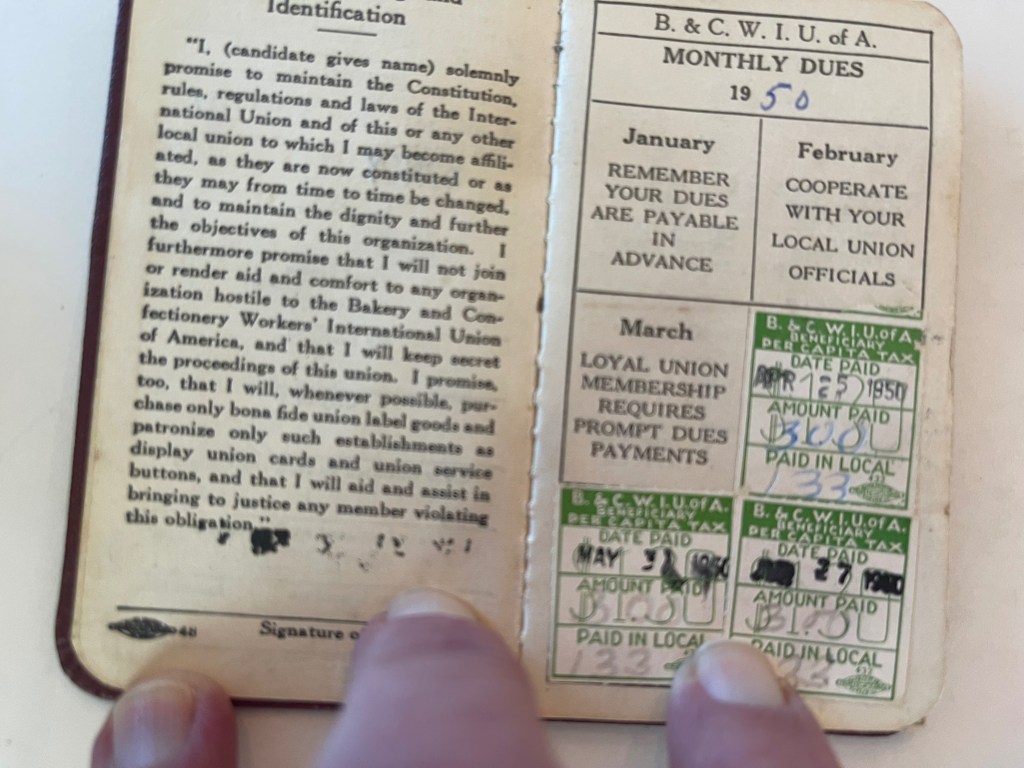

When he became a bakery owner his views on the union soured. The five top official of the International bakers union were indicted for embezzlement and conspiracy in 1958. After the AFL (craft unions) merged with the CIO (the industrial unions) in 1955 this new body expelled the baker’s union because of its reputation for embezzling and for requiring kickbacks from employers, also in 1958. The AFL-CIO set up a rival baker’s union, that fought tooth and nail with the original bakers’ union. That inter-union war lasted until 1978, when the rival bakers’ unions merged. The language in the union loyalty oath, “I furthermore promise that I will not join or render aid and comfort to any organization hostile to the Bakery and Confectionary Workers’ International Union of America, and that I will keep secret the proceedings of this union”, in the photo below can to be understood in the context of warding off any potential rival bakers’ unions.

While in high school I got to repeat some of my father’s experiences as bakery apprentice, albeit not at his Dickensian level. I also did the jobs that no one else wanted, such as mixing large vats of sour by hand. I got to work in many bakeries. My father wanted me to learn the business. One thing that puzzled me from my work across the town was the differences between the two union locals in Detroit that belonged to the same national union. These locals were known informally as the Jewish local and the Polish local, due to who originally had worked in them. In the 1920s you needed to speak Yiddish to be understood in one and Polish in the other. By the 1960s most of the bakers were neither Jewish nor Polish. Many were blacks. The term African Americans wasn’t used back then.

What puzzled me was that the wages were higher in the Jewish local, but that workers could move freely from one local to the other. When I got to college at the University of Michigan in 1965 I majored in Economics and took a class on labor economics. That class required an original research paper. My first, never published, paper was about the paradox of higher wages in one local, in spite of the free movement between the locals. Economists love paradoxes, especially if they turn out to have a logical economic explanation. My Dad got the union stewards at both locals to agree to me visiting a bunch of bakeries in the Jewish and the Polish locals. In each place I used a stop watch to measure how long the same task took. Hand bakery shops are very much team work. A baker who is slower than the other bakers in a shop will slow everyone else down, because the work is passed from one station to another. What I documented was that the workers were slower, say in making Kaiser rolls, in the Polish local than in the Jewish local. As workers got older and slowed down they preferred working in bakeries that were staffed by the Polish local because there was less pressure to keep pace. Conversely, anyone who was faster than the other bakers on the Polish side, would switch to the Jewish one.

While I was an undergraduate, I would still come into the bakery to let my Dad have a day off. When I went into the PhD program in Economics at Michigan State University, I would continue to come in to Detroit to spell my Dad. Over time his bakery got bigger by buying the adjacent buildings (these were three story apartment buildings with retail on the ground floor). The additional floor space made room for additional ovens and mixers and for more workers. At its peak the Frederick Model Bakery had 30 workers. What had originally been a small retail bakery became primarily a wholesale bakery selling mainly to restaurants. We were fortunate that two major expressways had exits near our bakery, which made it easy for independent bakery truck drivers to stop at our bakery.

One reason that my father disliked the union was that he had to take whomever the shop steward sent to work at his bakery. Some of the worst bakers spent more time arguing than working. One had a drinking problem. In an infamous incident he went to a nearby bar for a nip after he had filled an oven with the last load bread for the day. The bread needed 30 minutes to bake. His single nip became two or three and he forgot about the oven full of bread. After that incident his nickname became “cabbage head”. No one would leave him alone in charge of a full oven. Obviously, the difference between a bakery making or losing money depended on whether its workers were cabbage heads.

There were a lot of reasons I decided against taking over my father’s bakery. I was used to the long hours and the murderous heat in the summer. I even liked baking. My chief negative was how dangerous Detroit had become. Ours was a strictly cash business. Every morning around 9:00 AM my Dad, or me when I subbed for him, would take the day’s cash to the car. We were safe enough inside the bakery during the night, as there were usually a half dozen delivery drivers at any time inside the bakery picking up their goods. They were all armed. Taking the money from the bakery to the car after everyone was gone was another matter. One time my Dad was jumped on the sidewalk by a man with a large knife demanding the small paper bag my Dad was carrying. Instinctively, my Dad wrestled with the man, disarmed him, and chased him away. My Dad had forgotten that small bag had only a sandwich. After that attempted robbery, my Dad was always armed. He started with revolvers, but decided that he needed something more intimidating for his end-of-workday walks to the car. The intimidation was provided by a pump action sawed-off shotgun. I wound up carrying it too whenever I subbed for my Dad.

After the Detroit riot in 1967, in response to the police closing down an illegal after-hours bar (in street parlance a “blind pig”), large sections of the city were burned down. During the riot my Dad kept the bakery open under the exceptions provided by Governor Romney to essential businesses. There was no way my Dad would leave his bakery unprotected. Always practical, when the Michigan National Guard came in and then, when they were insufficient to control the riot, when President Johnson sent in 82nd and the 101st Airborne Divisions, my Dad sold fresh breads, rolls, and pastries to the soldiers.

Inner city Detroit had been like the wild west before the riots, hence our need for conspicuous deterrence. After the riots the city became a dystopian nightmare. The movie RoboCop was set in Detroit because of its reputation for violence. My Dad kept the bakery going until the late 1970s. After quadruple bypass surgery, even he decided it was enough. Between a possible future with heart problems, the constant danger, and the headaches of dealing with cabbage heads, I decided not to take over the bakery. We couldn’t find a buyer. The real value of the bakery was based on having someone who knew how to run it and was willing to work 12 hour days, six days a week. The equipment had very little value because it was too big for a small retail bakery and too small for a modern industrial bakery. It was also very old and needed constant maintenance. Buildings in Detroit could be bought from the City for whatever the property owed in back taxes. For years after the riot people would burn down their own buildings because the insurance value was more than the market value. Fortunately, my parents had saved enough to have a comfortable retirement.

I started my first academic job at the Indianapolis campus of Indiana University in 1974. After my Dad retired, my Mom and Dad bought two condos. One in Miami near my sister and one in Indianapolis near my house. That way they could spend time with both sets of their grandkids, in summers up north and winters in Florida. My Dad baked constantly at both homes. He would wear out home ovens and mixers before their warranties expired. His children, grandchildren, friends, and neighbors were never short of bread. On vacations he would visit bakeries abroad and try to learn how they made their local breads. He now had time for lots of travel. Not speaking the local language never daunted him. He would talk to French bakers to learn how they made baguettes or Israeli bakers to learn how they made pitas. He died at age 87 in 2002. My Mom, lived to the age of 101 until July 2024. For her last ten years she lived half the year with me and half the year with my sister. Because my Dad did all of the bread baking, she specialized in pastries and, of course, Hungarian cooking.

Below is a photo of my Dad saying the blessing for bread at our son’s Bar Mitzvah in 1988 over a large challah he had baked. The second photo is of me with a challah at my grandson’s bar mitzvah in 2024. The third photo is of me doing the same thing at my nephew’s wedding with a large challah I had baked in 2015. The last photo is Dad teaching our daughter and her fiancé how to make bread in 2001.